- » SURVEILLANCE & ART IN LATIN AMERICA [CALL]

- » CURATORSHIP TEXT

- » TEXTO CURADORIA

- » BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

- » ABOUT THE AUTHORS

- » IMAGES SOURCES

[CALL: WORK IN PROGRESS]

Hemos hecho desde 2010 una cartografia de trabajos de

artistas (y/o activistas) que explotan el tema de la vigilancia y del

control por medio de distintas estrategias.

Grandes panoramas del que se llama Surveillance Art (o Sousveillance)

se realizaron con éxito en paises de Europa y Norte America, reuniendo

la producción de artistas (y activistas) oriundos de estos continentes.

Sin embargo, poco se sabe sobre los trabajos desenvolvidos en este

campo en los países de Latino-america, donde el tratamiento de

este tema toma un camino própio, relacionado a las complejas realidades

sociales y históricas de la region.

En este sentido, convocamos artistas de videoinstalación, circuitos de

video, videoarte, nuevas midias, performers, activistas y personas que

trabajen con vigilancia, contra-vigilancia, RFIDs, GPS y otros

dispositivos a enviaren a nosotros un email con la

dirección electronica para

que podamos mapear sus trabalhos, y así seguir el mapeamiento de lo que

se estas produziendo en la región en estos 10 primeiros años del siglo

XXI.

Les agradezco desde pronto la divulgación de esta convocatoria y ayuda.

Contacto: surveillance@manifesto21.com.br

Surveillance Aesthetics in Latin America

This on-line exhibition presents a small selection of works by Latin American artists who incorporate in their creations technologies traditionally linked to surveillance and control processes.

By Surveillance Aesthetics we understand a compound of artistic practices, which include the appropriation of dispositifs such as closed circuit video, webcams, satellite images, algorithms and computer vision, among others, placing them within new visibility, attention and experience regimes (Bruno e Lins 2007; 2010).

The term referred to in the title of this exhibition is intended more as a vector of research than the determination of a field, as pointed out by Arlindo Machado under the term “surveillance culture” (Machado 1991). In this sense, a Latin America Surveillance Aesthetics exhibition is a way to propose a myriad of questions, starting from the works presented here. How and to what extent do the destinies of surveillance devices reverberate or are they subverted by market, security and media logics in our societies? If, in Europe and the USA, surveillance is a subject related to border control and the war against terror, what can be said about Latin America? What forces and conflicts are involved? How have artistic practices been creating and acting in relation to these forces and conflicts?

Successful panoramas of so-called Surveillance Art have already been

taking place in Europe and North America for at least three decades,

with the exhibition “Surveillance” at the Los Angeles Contemporary

Exhibitions being one of the first initiatives in this domain (Machado

1993). In 2010, a special S&S issue on "Surveillance, Performance

and New Media Art” presented a series of articles discussing several

topics related to art and surveillance, presenting different

experiences and practices of what Andrea Brighenti (2010) would call

“Artveillance”. But if Brighenti admits that in his analysis

he pays less attention to an “aesthetic of surveillance”, as defined

by Roland Schöny (2007 apud Brighenti 2010), we will here assume

aesthetics in its diversity as a key to understanding political and

social contexts in the continent.

In Latin America, art produced in the context of surveillance

devices and processes has been modestly analyzed by academics and

curators. Our intention is to assemble a selection of works indicating

the existence of a wider base of production that cannot be considered

occasional and needs to be investigated.

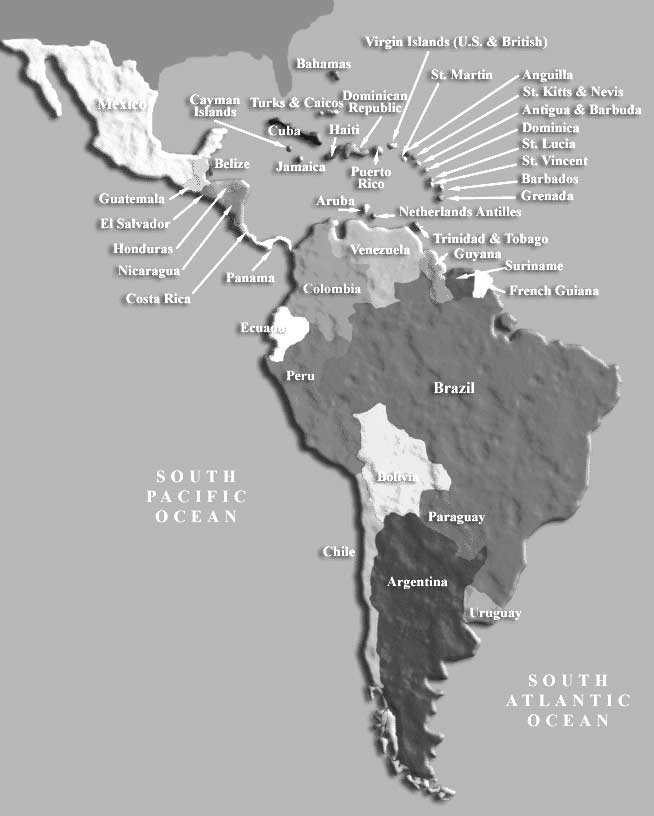

The body of works that composes this exhibition is, therefore, a partial result of a composition of perspectives in a much more complex and broader territory than this small presentation offers. A first cutout describes a context – Latin America. However, although this context coincides with a relatively defined geographic space, there is no possible uniformity in the creative, aesthetic, social, political and cultural fields (Mariátegui 2004). The connections between art and surveillance in Latin America do not compose a unified design in our presentation. We perceive areas of contact and dialogue as well as contrasts among perspectives, languages and distinct provocations. A chronological limit unites them and thus creates a second cutout: all the works in the exhibition were elaborated in the first decade of the 21st century, a decade marked by the multiplication and diversification of surveillance technologies in both public and private daily life, border control, social dynamics, etc.. Concentrating the works within this time frame indicates a desire to understand how these artistic practices appropriate or respond to the distributed presence of surveillance technologies in the “heat” of their moment. Inside this temporality our last cutout consists of a selection of only 11 works. An attempt is made to diversify the scope of the countries represented and the artistic proposals to the greatest extent possible in order to reach, albeit modestly, the Latin American plurality.

We hope that the works assembled here can point to “tactical indicators” (Foucault 2004, 5) in the terrain of force fields through which the present surveillance processes flow. How do such works perceive these force fields, their tensions and their obstacles, as well as their fractures, their failure zones and their margins of action? How do they manifest this perception? Which aesthetic, political, sensorial and cognitive circuits do they activate? To what extent do they produce fissures and interference in the control and spectacle circuits dominant in the present surveillance dynamics in the Latin American context?

This On Line Exhibition

The works in this exhibition “respond to” or “address” the questions above in different ways, dealing with distinct surveillance aesthetics. We notice, however, a predominance of CCTV among the selected works. A video circuit is defined as a technical-visual complex where images are captured in a determined space and projected on a monitor or screen, usually in real time. This technology – which has been popularized in middle- and high-class apartment buildings as well as in favelas, or shantytowns, under the control of drug dealers in Latin American metropolises 1 – has been used in contemporary art since the 60s.

As defined by Ricardo Basbaum when referring to his series Sistema-cinema

(2001-2010)

“a certain regime of the economy of the image and its functioning is

implemented" with closed circuit video, "side by side with the limits

and borders of the installation space." (Basbaum 2009, 263). Basbaum

develops a work where he combines gallery and museum interventions,

which the visitor can penetrate, cross and observe. In these works he

installs cameras and monitors in closed circuit, allowing access/vision

to points of view that the spectator/interactor could not experience

with the “naked” eye and body. His intention is to “trigger at the

installation site the presence of the mediation space, that is, to

produce membranes on the spot, right there” (Basbaum 2010a, 69) and “to

cultivate tools for building the contextual action in present time”

(Basbaum 2010b, 51). Besides the addition of layers of space and time

in the installation, Sistema-Cinema also operates a way of registering

and archiving for future usage, thus attributing an additional

potential temporality to the work.

The reflexive-participative dynamic introduced with the CCTV apprehends

the spectator’s presence and turns him/her into part of the

work/installation. This is also explored in different ways in the works

of Gustavo Romano and Alfredo Marquez.

In Pequeños mundos privados (2001), Argentinian Gustavo Romano presents a prepared microscope where the viewing lens has been replaced with a sort of camera viewfinder. Once the visitor gets closer to examine, he/she is surprised by his/her own image looking through the microscope. The image is captured on a camera, which is behind the viewer, thus combining notions of scrutiny and imprisonment. In this closed circle there is no strict need to record the images and nothing to be seen aside from the fact of observation. The camera captures the spectator inspecting inside the microscope the image that the camera (macroscope) captures: tautology. It is the very act of observing oneself observing that is at stake, as are the limitations of such observing; this is all expressed in a vision of one’s own image, from the back, in the shadow of a stalking camera.

Peruvian artist Alfredo Marquez and Coletivo Peru Fabrica create with (Des)instalacion Ecce Homo (2000) an ambient of confrontation and confinement, where CCTV provokes tensions between the space that exhibits and that which imprisons, the act of seeing and that of being seen, the interior and the exterior. Two monitors, a computer connected to the Internet and a red line with names of prisons in Peru are displayed in a dark room. One of the monitors shows a sequence of CCTV images from a room simulating a cell, where an actor performs restricted actions of everyday prison life – exercising, sleeping, eating. (The actor and Marquez were political prisoners in the same institution during the 90s, during the Fujimori regime). The second monitor shows images in real time of the exhibition visitors in the darkened room, duplicating their gaze in confrontation between their own image and that of others, between the installation space and prison space. Alongside the two monitors, a computer shows a website with documents from an ad hoc commission for prisoners unjustly confined in Peru. A webcam connected to this computer captures the image of the visitors analyzing the documents. The spectators see themselves once again in the position of seer/seen, but now before another kind of “space”: the informational flow of the Internet, whose reticular and distributed architecture allows them to escape the hierarchic contentions of archives traditionally restricted to power circuits and their institutions.

Dolores de 10 às 10 (2002) reassumes elements of Marquez’s work, such as re-enactment, confinement and political violence against bodies. However, in this video installation by Cuban artist Coco Fusco, the “prison” is the factory. This piece is the result of research by the artist in a “maquiladora”1, known for disrespecting workers’ rights, located in Tijuana, Mexico. The city is on the border with the USA, a zone under strong surveillance, including video-monitoring. There are strict restrictions on the movement of Mexican citizens, but the same cannot be said about the industrial products assembled in the “maquiladoras”. In this installation Fusco invests in the reconstitution of CCTV footage, re-enacting facts that happened to Delfina Rodriguez, “a maquiladora worker who had been accused by her employer of trying to start a union in the plant. To coerce her into resigning, her manager had locked her in a room without food, water, bathroom or phone for twelve hours.”2 She tried to sue her former employer for violating her civil rights, but she could not prove what she had been put through. In this context the artist recreates images that CCTV could have recorded. The installation thus produces a “fictional proof” of her internment, at the same time attesting to the fictional nature of any proof and subverting the visual hierarchy in which CCTV is usually included.

This sense of surveillance reversion, or shattering, when it is not even possible to say from and to where it is being exerted, is what we want to underline in the work of Lucas Bambozzi and Paloma de Oliveira. Also conceived as a reenactment of an event – the attacks that the criminal organization PCC ordered in São Paulo – Do Sofá da sua casa (2010) presents an installation consisting of a video-mapping in a domestic scenario, thematizing the production of images within a network and creating an experience of shared tension of “the day that São Paulo stopped”3. The event that is the matrix of the work brings the elements of a shattered landscape, in that the actions coordinated around the city were orchestrated overall via phone calls originating from within the prisons. A place of surveillance, reclusion and control par excellence thus became the basis for communications and actions against Latin America’s largest city. Blatantly exposing the fragility of the Brazilian prison system, the episode casts shame on the promoters of mobile networks when it gains a visibility and a propagation that publicity campaigns could never produce. In addition to this, the media’s capitalization of panic – above all by television – amplified the chain of images and senses linked to the events. In this work the problem of the veracity of visual recordings in a context in which surveillance processes cannot be dissociated from the spreading of quotidian vision and recording technologies reappears. Instead of the emblematic CFTV, cell phones and media images compose networks which propagate images and discourses whose connections are at the same time of control and decontrol, power and anti-power, surveillance and “sousveillance”, entertainment and panic.

Marcela Moraga is also interested in the phenomena of spectacularization of reality and fear. Moraga integrates the group Testigo Ocular, a project created by Chilean artists to foment exchanges between Chile, Latin America and abroad. Living in Germany as an artist-in-residence, Moraga works with urban interventions and photography, proposing a critical look at the post-09/11 scenario. Her work La vida es un gran cine (2007) refers in an explicit way to a publicity slogan used by Chile Telecom company. If, on the one hand, it refers to a romantic ideal that compares life and film, on the other it is haunted by the idea of the continuous televising of places, suffocating the potential experience of anonymity in public space. Confronting a surveillance camera in a subway station with an amateur video camera, Moraga provokes a short in two different circuits and makes evident the intersecting spheres of surveillance and publicity in a photo where she registers the act of watching the watchers. In this intervention the artist adopts a silent strategy, setting an ephemeral scene protagonized not by actors or spectators, but by the dispositifs.

The intervention in public and semi-public spaces, provoking connections between the seduction of the spectacle and the paranoia of surveillance, resurfaces in the work of the Brazilian collective mm não é confete, Performances Panopticadas/ Surveillance Wireless Vj'ing Performance – work in progress (2003-2006). A series of performances by the collective overlap the already noisy urban space of São Paulo with images and sounds in real time with the saturation of contemporary media and surveillance images. Images of interaction with the public are captured by a micro-camera attached to the wrist of the performer (whose makeup à la Blade Runner is like a bleak future dejá vu) and reworked live by VJs mixing pre-recorded images. The resulting live mix video is re-projected in real time in the performance space as well as on an LCD screen attached to the performer’s chest. Added to this spiral of sounds and images is the “mantric” repetition of concepts that harness surveillance, spectacle and consumption (mm não é confete, 2004), seeking to awaken attentional focus in the midst of the multimedia dispersion flooding the ambience. The interaction of the public, incited to dialogue with that which surrounds them, compose a performance manifesto, shuffling time, speech and media.

The presence of the spectator as part of the work reappears in Modular Solution for Corridor Reactive Installations (2009) by the Colombian Andrés Burbano. This occurs, however, according to an algorithmic logic and from a corporal presence, taken above all in its motor-sensory dimension. It is an installation that uses a video circuit in real time as a source of “inputs”, but the derived images from this inflow are projected using “computing optics” mixed with pre-programmed algorithms, position and distance sensors that scan the spectators’ bodies in the space. What we see are forms and lines generated by these diverse filters that are added to the captured image. Even though this is not a reference or explicit preoccupation of the author, the system created by Burbano reminds us of the “newer” generation of video surveillance that couples algorithmic layers to the cameras, supposedly making them capable of detecting suspicious or threatening behavioral movement.

The relationship between the occupation of public space, bodies and monitoring technology is represented in Sandbox (2010), an interactive installation developed by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer for the Glow Santa Monica festival in California, USA. Installed on the beach like a large fairground attraction or open-air cinema, the work consists of two boxes of sand that allow the public to participate in three dimensions: a miniature projection, a human scale and an amplified projection on a huge scale. The images give feedback in a virtuous cycle: the smaller figures place themselves in a game with giant figures, producing a circularity of projections that captures and recaptures images. By creating what he calls “relational architecture”, Lozano-Hemmer appropriates video-surveillance as an element capable of potentializing the sharing of space, transforming the asymmetrical relation between the watchers and the watched into the raw material for a new kind of shadow theater. As the artist himself describes, the equipment used in Sandbox refers to that which is used on the North American-Mexican border to track illegal immigrants, just as video circuits in shopping centers track adolescents. However by turning a space under surveillance into an area of play, performance and stage, Lozano-Hemmer reverts the dispositif, and creates an environment where people are connected, as opposed to a space of suspicion and segregation.

Anibal Lopez also executes his work in public spaces, but without the guidelines of festivals or official agendas. The Guatemalan artist – who signs his works with the inscription A-1 53167, a reference to his ID registration – carries out clandestine acts that disrupt order and place in order to question freedom of expression and the limits between art and activism. His work 30 de Junio, 2000 (2000) took place over only one day and combined urban intervention and photography. In a rapid nocturnal operation, A-1 53167 spread the contents of ten sacks of coal across the principal avenue in downtown Guatemala City, where a military procession was programmed to take place the following day. Despite the coal having been removed, a black stain remained on the road. The boots of the marching soldiers inadvertently spread the coal dust, and the resulting trail created by their footsteps was recorded on his camera. In this way the artist produced a work not involving actors or spectators, but the very military forces of Guatemala – responsible for repression and violence against the population during almost forty years of civil war. The choice of coal is not only due to the fact that it served as “ink” for the soles of the soldiers’ boots. As the artist explains, coal can be found in mass graves and in the houses and on bodies burnt by death squads connected to the military. By introducing coal to the parade site, A-1 53167 produced a counter-surveillance action that reveals acts the state prefers to conceal.

The “vestige” of embarrassment, felt by those in confrontation with representatives of “authority”, is subtly and acutely captured in the video Teoria da Paisagem (2005), by the Brazilian Roberto Bellini. The first images of the video – an airplane crossing the sky, the sun setting on the horizon, birds flying – do not differ greatly from those that follow until the end. In voice off we hear dialogue from which we deduce that the artist is being confronted by a security guard and interrogated about his intentions and warned about the dangers of filming: “the police are very nervous about this sort of thing”. The involvement of the guard confers a dimension to the act of watching and filming that is absent from the innocent and contemplative landscape images of the video, yet very present in the quotidian of urban and media landscapes. Whereas the apparatuses of surveillance proliferate in public areas, legal restrictions are imposed on the cameras of artists, journalists and amateurs, who are placed under suspicion by current security policies. The artist, in turn, has the astuteness to make this unexpected disruption of his work part of the artistic presentation. “The dialogue has the force of something that does not happen twice, and the artist has the insight to maintain this in tension...This is the patience and intelligence of the work: allow the text to surpass communication and make vibrate a state of world” (Migliorin, s/d). Bellini sidesteps surveillance by producing a type of ellipse that documents it, causing within it a trace, a “proof”, that turns against that which created it, in a poetical-critical movement.

The works presented here in many ways update processes and aspects regarding surveillance mechanisms in contemporary societies. Such processes quite certainly have global dimensions, but they also echo particularities of the Latin American context. While some works recover the marks that still remain from the authoritarian regimes that governed the region in the second half of the 20th century, with historical themes of surveillance and violence such as prisons and military forces, others present more recent dynamics of the Latin American scenario, especially dynamics related to security and spectacle. In Latin America, the insertion of surveillance technologies in everyday life is linked to security policies, public as well as private, which expanded markedly as of the 90s and gained new breath in the first decade of the 21st century. These policies go hand in hand with the rise in crime rates and the feeling of insecurity in urban centers, making the security rational a principle of social life order (Botello, 2009). In this scenario, the state apparatus usually takes on the role of fighting crime and controlling populations deemed dangerous. In the Latin American context these populations coincides with lower income groups living in urban areas marked by different precarious conditions: sanitary, educational, social, etc. In the private sphere, the demand for property and individual security feeds a whole apparatus that includes the real estate market, security industry and urban gentrification processes (Kanashiro, 2008). This apparatus is dedicated to protecting middle and upper-class populations considered potential victims of urban crime by equipping neighborhoods, condominiums and residential buildings where these populations live with surveillance and security systems. CCTV systems, very evident in the works of art presented here, flooded Latin America by means of the private security industry that protected private and/or commercial areas against the threat of populations deemed dangerous. As Marta Kanashiro (2008) points out, considering the Brazilian historical context: "surveillance cameras in Brazil passed through some reconfigurations of meaning, during which security began to be seen as a commodity and as something to be provided privately(…) Cameras are seen as part of a process of urban transformation characterized by social exclusion.” (Kanashiro, 2008, 9)

One can thus observe that such devices are tied to a context of inequality, violence and social segregation expressed in some of the works presented in this exhibition. Another face of the Latin American culture of surveillance that is also present in the works presented consists in the strong impression television culture has on the everyday life of several Latin American countries. In news broadcasts as well as in entertainment programs, video surveillance images are recurrent and appear either as an index of what is “real” or as a narrative resource that lends an authenticity to television’s worn-out credibility and “restores” the viewer’s attention. The presence of video-surveillance images in Latin America’s midiatic rhetoric contributes to the trivialization of these devices in social life as well as increases its value in the (in)security market.

While this scenario is more explicitly present in some of the works of art, others attempt to explore aesthetic, emotional and sensorial processes that enhance, subvert and contort the senses and habitual social uses of security devices. In any case, if the securitarian or spectacularized logic of surveillance saturates our perception and regimes of vision and registration under control, the works presented here point to fissures and virtualities that problematize the limits within this logic. We hope that the reflexive, sensorial and participative processes incited by such works can dialogue with the academic research present in this issue, thus broadening the margins of contact between aesthetics, thought and politics.

This exhibition began from a mapping proposed by Manifesto21.TV in the beginning of 2010, with the aim of relating the production of Latin American artists and activists. This mapping, coordinated by Brazilian researchers and artists Milena Szafir and Paola Barreto, includes approximately 30 artists and is still in progress2. The section presented here is the result of a connection between this initiative and the research of Fernanda Bruno, Ph.D., about surveillance aesthetics, developed since 20063. We would like to thank all the artists and collaborators.

Estéticas da vigilância na América Latina

Esta curadoria on line apresenta uma pequena mostra de trabalhos realizados por artistas latinoamericanos que incorporam em suas obras tecnologias cujas funções sociais são tradicionalmente atreladas a processos de vigilância e controle. Por Estéticas da Vigilância entendemos um conjunto de práticas artísticas que incluem a apropriação de dispositivos como circuito fechado de vídeo, webcams, imagens de satélite, algoritmos e visão computacional, entre outros, inserindo-os em regimes próprios de visibilidade, atenção, experiência (Cf. Bruno e Lins 2007; 2010). O termo que dá título a esta mostra pretende ser menos a descrição de um campo determinado do que um vetor de exploração, como também apontado por Arlindo Machado sob o termo “cultura da vigilância” (Machado 1991). Neste sentido, uma mostra sobre estéticas da vigilância na América Latina é um meio de propor, a partir dos trabalhos aqui reunidos, uma rede de questões. Como e em que medida se reverberam ou se subvertem os destinos que a lógica securitária, mercadológica e midiática reservam aos dispositivos de vigilância em nossas sociedades? Se nos EUA e na Europa a vigilância é um tema que se articula, por exemplo, à guerra ao terror e ao controle dos fluxos migratórios, o que podemos dizer da América Latina? Que forças e conflitos estão em jogo? Como as práticas artísticas têm criado e atuado no âmbito dessas forças e conflitos? Importantes mostras do que se convencionou denominar de surveillance art ocorrem nos EUA e na Europa há pelo menos três décadas, sendo a exposicão “Surveillance”, realizada em 1987 no centro Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, uma das primeiras iniciativas neste sentido (Machado 1993).1 Na América Latina, contudo, a arte produzida no diálogo com dispositivos e processos de vigilância ainda é vista como novidade ou evento isolado, e a intenção aqui é justamente reunir obras que apontam para uma produção ampla e diversificada, longe de poder ser considerada eventual. O conjunto de trabalhos que compõem esta mostra on-line é, assim, um resultado parcial de um conjunto de recortes sobre um território bem mais complexo e vasto do que esta pequena apresentação põe em cena. Um primeiro recorte delineia um contexto – o latino americano. Mas se este contexto coincide com um espaço geográfico relativamente bem demarcado espacialmente, não há, no plano criativo, estético, social, político e cultural uma uniformidade possível (Mariátegui 2004). As conexões entre arte e vigilância na América Latina não constituem nesta mostra um desenho unificado. Assim, entre as obras percebemos zonas de contato, de diálogo e também de contraste entre linguagens, perspectivas e provocações distintas. Uma demarcação temporal as reúne, instituindo um segundo recorte: todos os trabalhos desta mostra foram elaborados na primeira década do século XXI, marcada pela multiplicação e diversificação da presença de tecnologias de vigilância no cotidiano da vida pública e privada, na regulação das fronteiras territoriais, nas dinâmicas sociais etc. Concentrar as obras nesse limite temporal traduz um desejo de apreender como as práticas artísticas latino americanas se apropriam ou respondem a essa presença distribuída das tecnologias de vigilância, ainda no “calor” de sua atualidade. Dentro desta temporalidade, nosso último recorte consiste na seleção de apenas 11 trabalhos, buscando diversificar ao máximo tanto o escopo de países presentes quanto o de propostas artísticas, atendendo, ainda que de forma modesta, a pluralidade latino americana.

Esperamos que os trabalhos aqui reunidos apontem “indicadores táticos” (Foucault 2004, 5) no âmbito dos campos de força por onde se passam os processos de vigilância atuais. Como tais trabalhos percebem estes campos de forças, as suas tensões, seus obstáculos e também suas brechas, suas zonas de falência e margens de ação? E como eles traduzem essa percepção? Que circuitos estéticos, políticos, sensoriais e cognitivos eles ativam? E em que medida criam rachaduras e ruídos nos circuitos de controle e de espetáculo hoje preponderantes nas dinâmicas da vigilância no contexto latino americano?

Esta mostra on-line

As obras desta mostra “respondem” ou “encaminham” essas questões de modos distintos, colocando em jogo diferentes estéticas da vigilância. Percebemos, contudo, uma clara predominância da utilização do circuito fechado de vídeo entre os trabalhos selecionados. O circuito de vídeo se define como um complexo técnico-visual onde imagens são capturadas em um determinado espaço e oferecidas em um monitor, ou projeção, usualmente em tempo real. Esta tecnologia – que nas cidades latinoamericanas é popularizada nas portarias de condomínios de classe média e alta, ou mesmo nas favelas 2 - tem sido empregada na arte contemporânea desde os anos 1960 3. Como define Ricardo Basbaum a respeito de sua série Sistema-cinema (2001-2010), com o circuito fechado de vídeo “certo regime de funcionamento e economia da imagem é instaurado, junto ao espaço delimitado e fronteiriço da instalação” (Basbaum 2009, 263). Basbaum desenvolve um trabalho no qual combina intervenções em galerias e museus, criando arquiteturas específicas, as quais o espectador pode atravessar, penetrar, espreitar. Nestas obras instala câmeras e monitores em circuito fechado, permitindo ao espectador/interator a visão/acesso a pontos de vista distintos daqueles que pode experimentar com seu corpo e seu olhar “nus”. Sua intenção é “deflagrar no local da instalação a presença da dimensão mediadora, isto é, produzir membranas ali mesmo,” (Basbaum 2010a, 69) e “cultivar ferramentas para construir a ação contextual em tempo presente” (Basbaum 2010b, 51). Além da adição de camadas no aqui e agora da instalação, Sistema-cinema também opera como meio de registro e arquivamento para usos futuros, inserindo a obra uma temporalidade adicional, potencial.

[O TXT CONTINUA COM AS ANÁLISES DE CADA OBRA-ARTISTA E SEUS RESPECTIVOS LINKS - COMO ACIMA - A SER COLOCADO APÓS PARECER DA REVISTA: VERSÃO FINAL P/ PUBLICAÇÃO]

Se a lógica securitária ou espetacularizada da vigilância satura

nossa percepção e nossa atenção de imagens que se pretendem

finalizadas, inequívocas, cabais, criando regimes de visão e registro

sob controle, os trabalhos artísticos aqui apresentados apontam aí

fissuras e virtualidades que problematizam os limites desta lógica.

Esperamos que os processos reflexivos, sensoriais e participativos

incitados por tais trabalhos dialoguem com as pesquisas acadêmicas

presentes neste número, ampliando as margens de contato entre a

estética, o pensamento e a política.

Esta curadoria foi elaborada a partir um mapeamento proposto pelo

Manifesto 21 no início de 2010 com o intuito de relacionar a produção

de artistas e ativistas latinoamericanos. Este mapeamento, realizado

pelas pesquisadoras e artistas brasileiras Milena Szafir e Paola

Barreto, inclui hoje cerca de 30 trabalhos e ainda se encontra em

andamento. O recorte que apresentamos aqui é um resultado do encontro

entre esta iniciativa e a pesquisa da Profa. Dra. Fernanda Bruno sobre

estéticas da vigilância, desenvolvida desde 2006. Agradecemos a

participação dos artistas e colaboradores.

[BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES]

Basbaum, Ricardo. 2009. roteiro para sistema-cinema. In

Transcinemas, ed. Kátia Maciel. Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa.

_________________. 2010a. membranosa-entre (NBP): anotações, In

Conversas Itinerantes. Florianópolis: Conexão Artes Visuais – MinC –

Funarte – Petrobrás (catálogo de exposição).

Bruno, Fernanda e Lins, Consuelo. 2007. Estéticas da Vigilância. Revista GLOBAL Brasil, fev. 2007, 38-39.

Foucault, Michel. 2004. Sécurité, territoire, population. Cours au Collège de France (1977-78). Paris: Seuil/Gallimard.

Lins, Consuelo e Bruno, Fernanda. 2010. Práticas artísticas e Estéticas da Vigilância. In Vigilância e Visibilidade: espaço, tecnologia e identificação, ed. Fernanda Bruno, Marta Kanashiro e Rodrigo Firmino. Porto Alegre: Sulina, 43-53.

Machado, Arlindo. 1991. A Cultura da Vigilância. In Rede Imaginária: televisão e democracia, ed. Adauto Novaes. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

_______________. 1993 Máquina e Imaginário. São Paulo: Edusp, 1993.

Mariátegui, José-Carlos. 2002. The Camera as an Interface: Closed-Circuit Video Projects in Peru. Leonardo Electronic Almanac, March, 10 (3).

_______________________. 2004. Latin American Media Art. Leonardo Electronic Almanac, August, 12 (8).

Migliorin, Cezar. Landscape theory. Dossier 021 - Video Brasil, sem data.

mm não é confete. 2004. Manifesto Panóptico. São Paulo-SP

[ABOUT THE AUTHORS]

Associate professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) - Postgraduate Program in Communication and Culture. CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) Researcher. Visiting Researcher at CERI/Sciences Po and Médialab/Sciences Po, Paris (2010-2011).

Researcher in "surveillance+spectacle=consumption" and art-technology educator since the 90s. Master in Communication Science (with the "Audiovisual Rhetoric" thesis + the "Panopticon-Synopticon" installation) and PhD-student in MPA, both at University of São Paulo (USP). Ex-soccer player, graduated in Computer Science and Urbanism-Architecture, she's been producing content for the mainly digital-electronic culture festivals around the world during the 2000s.

paoleb is a visual artist, researcher and lecturer. Born in 1971, she lives and works in Rio de Janeiro and has been designing video circuits for film, theatre, performance and exhibitions since 2002. In 2009 she obtained her Master degree in Technology and Aesthetics at UFRJ with the thesis “Composition for Video Surveillance”.

[IMAGES SOURCES]

»Alfredo Márquez [Peru, 2000]: artist courtesy

»A-1

53167 [Guatemala, 2000]: 49o Biennal Venezia

»Ricardo Basbaum[Brazil, 2001-2010]: artist courtesy

»Gustavo Romano [Argentina, 2001]: artist' site

»Coco Fusco [Cuba, 2002]: artist' site gallery»mm não é confete [Brazil, 2003-2006]: artist courtesy & online video's frames

»Roberro Bellini [Brazil, 2005]: online video's frames

»Marcela Moraga [Chile, 2007]: artist courtesy

»Andres Burbano [Colombia, 2009]: artist' site

»Lucas Bambozzi e Paloma Oliveira [Brazil, 2010]: artist courtesy

»Rafael Lozano-Hemmer [Mexico, 2010]: artist' site